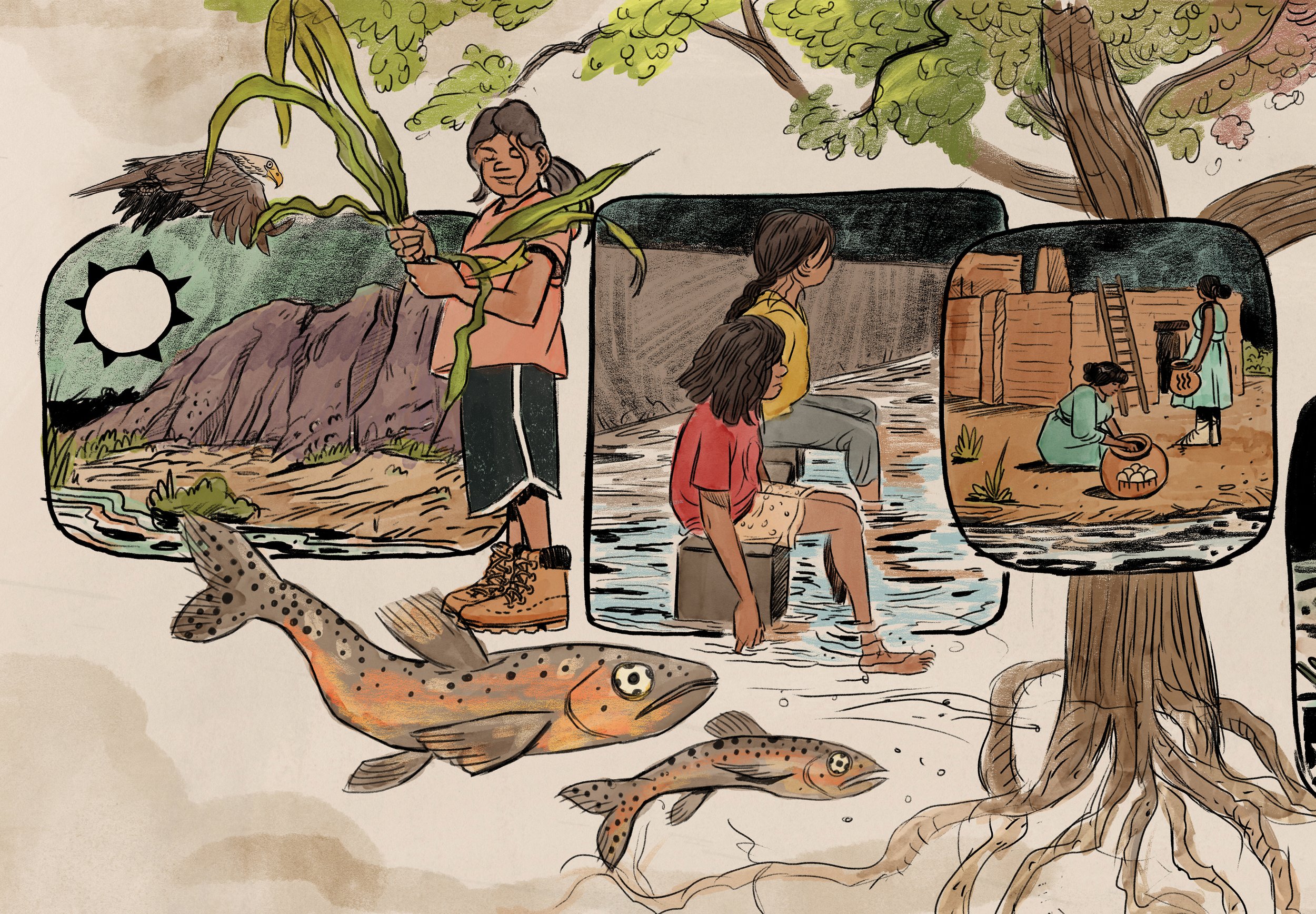

The River (Remix) Color Version | 2022

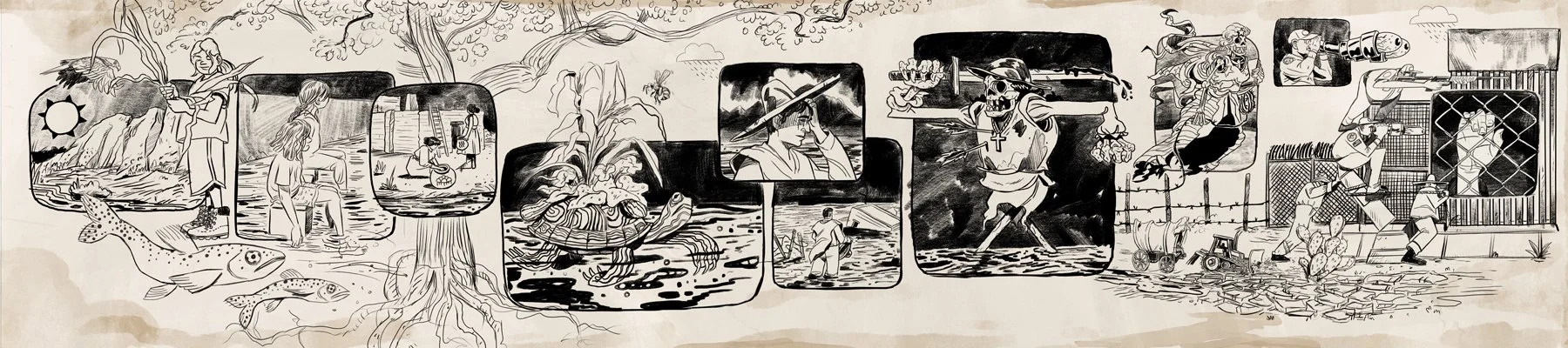

The River (Remix) 2022

The River (Remix) 2022 - Part I

The River (Remix) 2022 - Part II

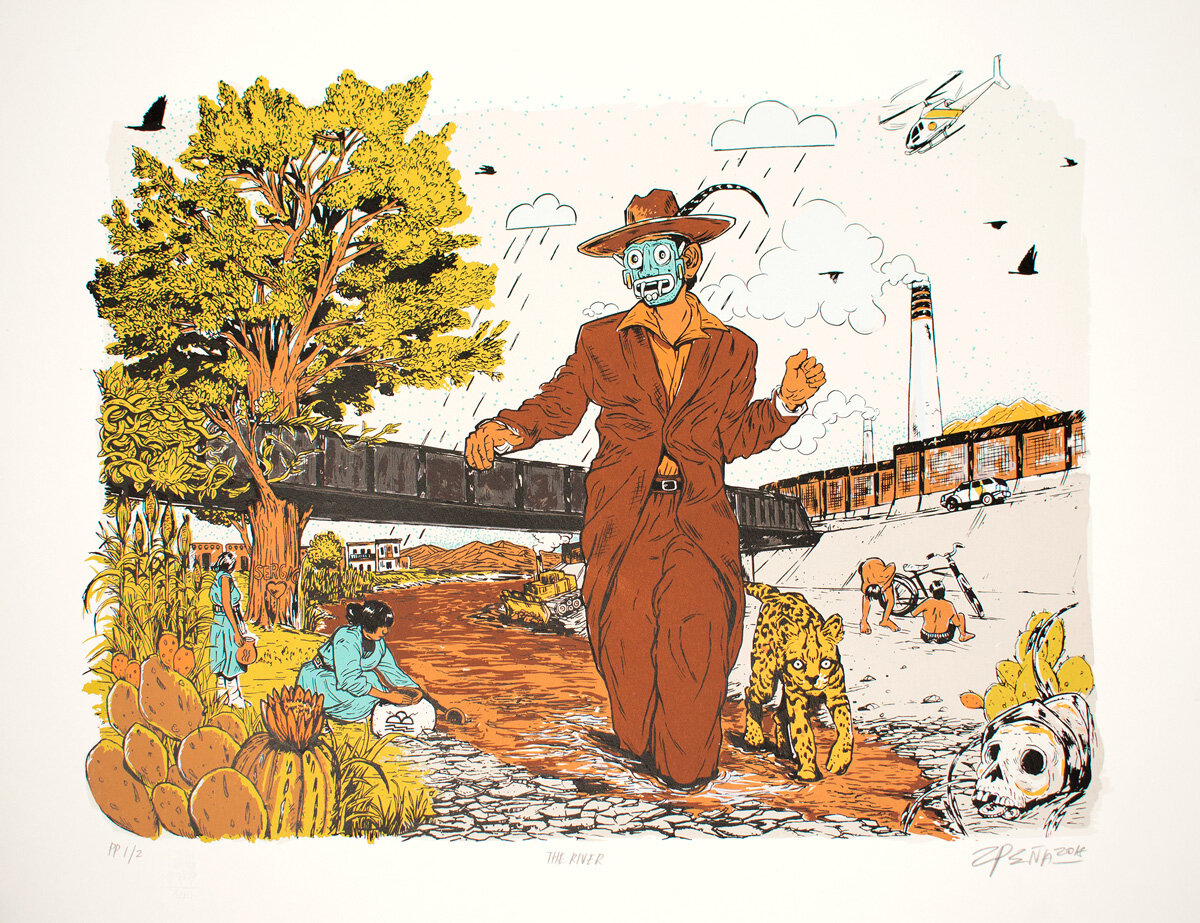

The River printed in 2018 at Self-Help Graphics was the image that was sampled in The River (Remix). | Serigraph; 12 Colors

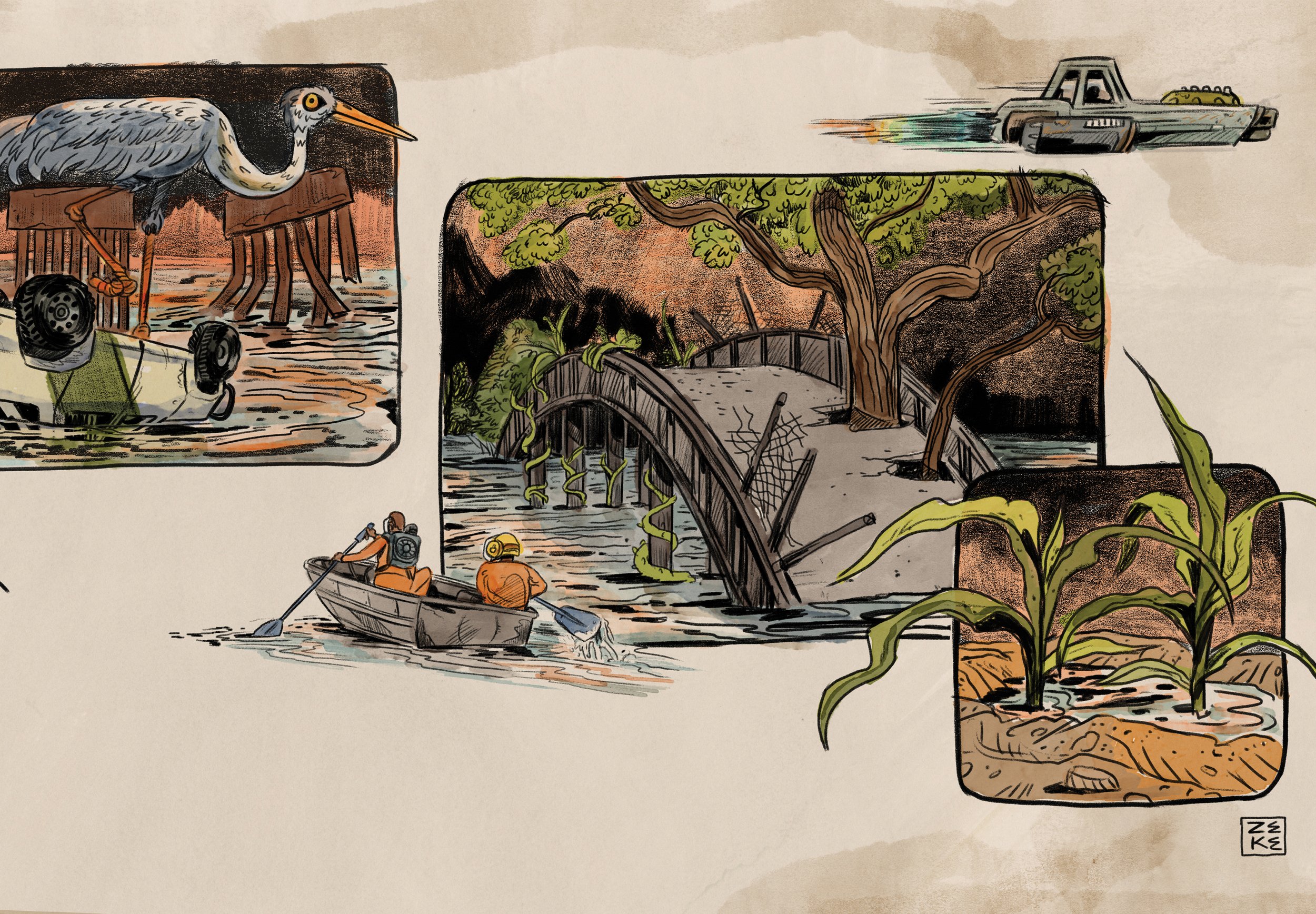

American Dam is just yards north of the place where the international boundary intersects the River. (© Zeke Peña)

RECLAIM THE RIVER Symbols and Satire in The River (Remix) by Zeke Peña

In the Chihuahuan desert on Turtle Island (North America), we instinctively understand the importance of water but most of us who live in this region are only familiar with faucet water and rain. Over the past several years, I have researched and made work about the River known as Peh-la, Rio Grande or Río Bravo. I’ve focused on the section of this sacred river that runs through what is known today as the Paso Del Norte Region in the Mexico-US borderlands. The significance of the River in our community, culture, and history is obscured by decades of erasure and border militarization. This section of the Middle Rio Grande is often referred to as the “Forgotten Reach,” a section of the River that is completely dry with the exception of seasonal irrigation allotments. It’s also here, yards past the American Dam, that the River begins being used as the line of demarcation for the international boundary.

I’m not a scientist or a hydrologist, but I’m interested in the cultural, social, and historical relationship the communities of the Paso Del Norte region have with the River. This special River has sustained my mother’s family in the Mesilla Valley for generations. But I didn’t grow up with a deep understanding or connection with the River. The history of colonized regions is broken, cloaked in myth, and often erased entirely—and this region has been colonized twice.

During a workshop with students from both El Paso, Texas, in the United States and Ciudad Juárez, Chihuahua, in Mexico, I confirmed what I know from my own experience growing up here: Our youth in this region see the river as a boundary first, then a river. Asking young people about the River uncovers a generational shift because so few of them have any memory of the river. Most of them have only crossed the River on one of the international bridges that connect the two countries. In contrast, elders in the community have significant personal memories that precede the construction of the concrete canal that channelized the River after the signing of the Chamizal Treaty in 1965. Their memories also precede the border wall that in recent years has been violently constructed against the will of our transnational community and to the detriment of Indigenous communities like the Ysleta Del Sur Pueblo (Tigua). The lack of knowledge and relationship with the River that increases with each generation leaves a void for the River space to be further occupied and destroyed. What we are experiencing today with a dry riverbed most of the year is not normal, because it wasn’t too long ago the River flowed wild and free.

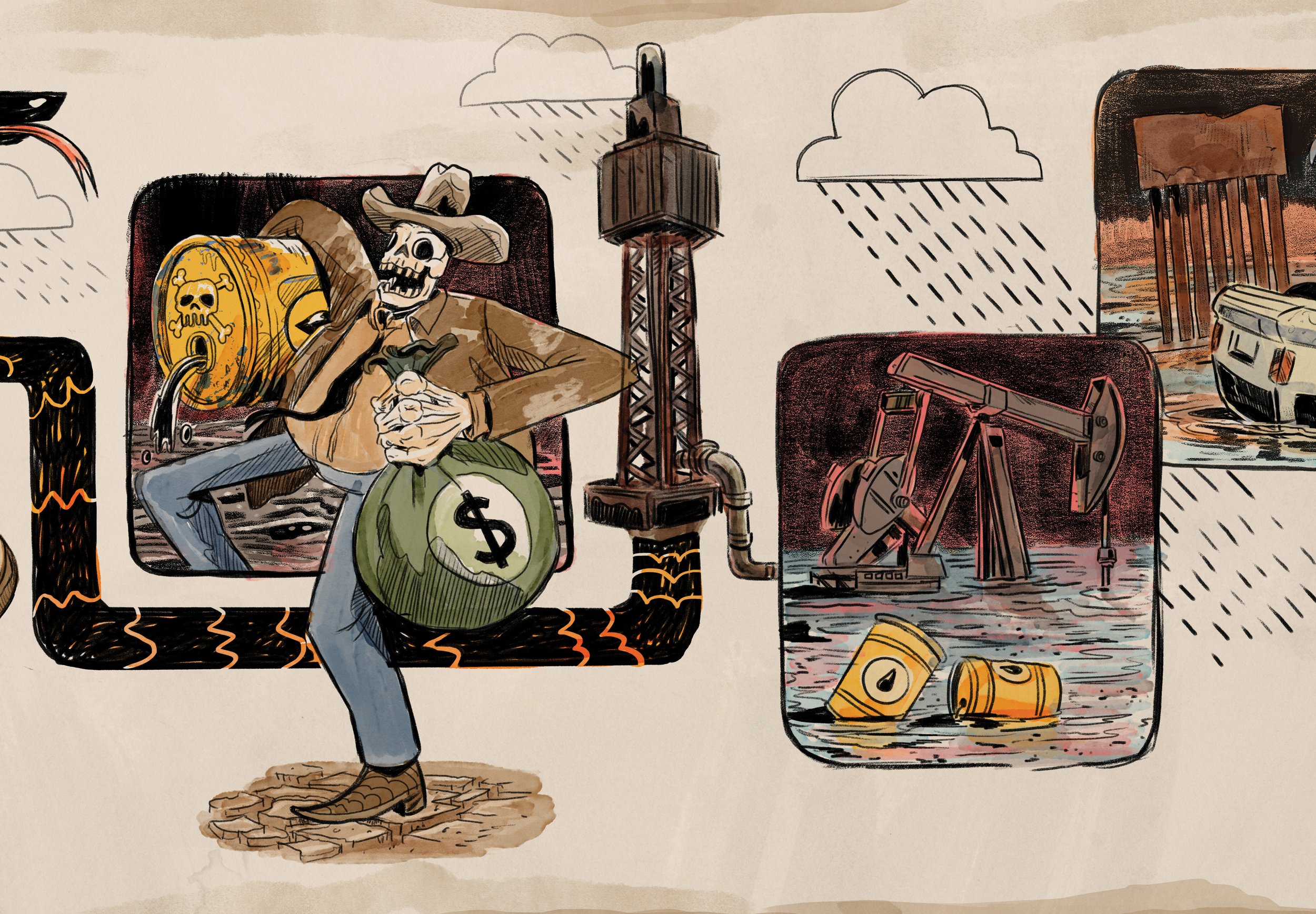

The River (Remix) is a panoramic comic in two parts that tells a visual story of the River in past, present, and future using images, symbols, and satire—telling a story of the River without words. The story is not objective, not comprehensive, and not linear but focuses instead on key moments in our relationship with the River. Similar to the work of José Guadalupe Posada, Leopoldo Méndez, and the printmakers of Taller de Gráfica Popular (Mexico), this comic uses satire to expose truths about the colonization, exploitation, and militarization of the River. The River (Remix) uses exaggeration and caricatures of calaveras (skulls) to highlight the detrimental changes inflicted on the river like Posada’s Calavera revolucionaria (Revolutionary Calavera, 1910) and Taller de Gráfica Popular’s Calaveras estranguladoras (Strangling Calaveras, 1942). The comic also illustrates actual people, places, and moments, including the sacred site known today as Hueco Tanks; the Indigenous people of Ysleta Del Sur Pueblo (Tigua); Spanish Colonization and Juan de Oñate’s river crossing; the doctrine of Manifest Destiny and American Colonization; the construction of the international border and border militarization; a march and ceremony in protest of the Trans-Pecos Pipeline; and the flood that changed my own family’s history in the region. This brief collection of visual-historical narratives is an attempt to remix truth back into our history, reclaim our shared story with the River, and reconnect to the River that sustains our community.

Some of these reflections first appeared on August 4, 2021, in the University of New Mexico Art Museum Journal written when I was an artist-in-residence at the Center for Environmental Arts and Humanities.